In 1958 David Oistrakh became the first official Soviet artist to perform in Australia. At a time when there were no official diplomatic relationships between Australia and the USSR, Oistrakh’s tour was not only a musically significant event but was also important in developing cultural cooperation and friendship between the two countries.

David Oistrakh holding the souvenir boomerang presented to him at Mascot upon his arrival, and Oistrakh's accompanist Vladimir Yampolsky. Taken from 'Soviet Violinist in Australia', The Canberra Times, 28 May 1958, 5. Accessed on http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article136298250.

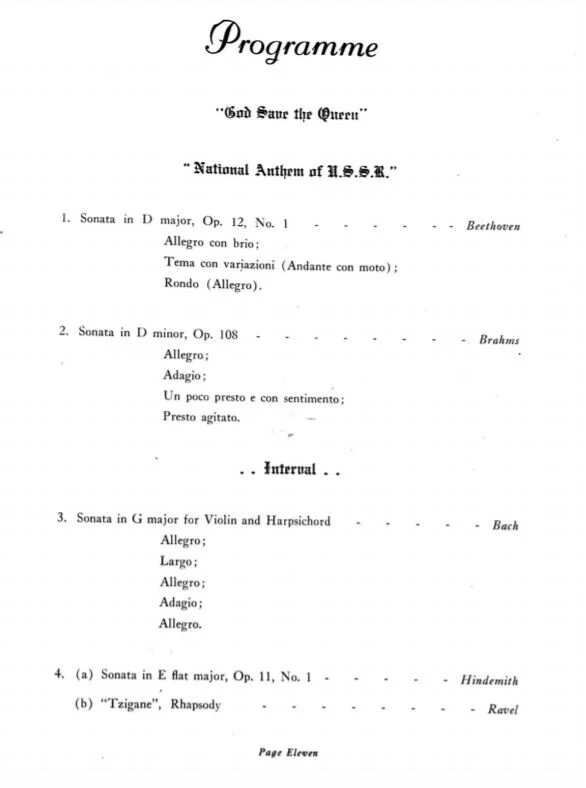

Oistrakh arrived in Australia on May 27th 1958, after his New Zealand tour. He came alongside his wife, accompanist Vladimir Yampolskiy, and secretary/interpreter Nikolai Arte(a?)mov. His main concerts were scheduled for Melbourne (May 29th, June 3rd, June 5th), Sydney (June 7th, 10th, 12th, 17th), Brisbane (June 14th), and Adelaide (June 30th). The works performed by Oistrakh and Yampolskiy included Beethoven's Sonata in D major Op 12 No 1, Brahms's Sonata in D minor Op 108, J. S. Bach's Sonata in G major, Hindemith's Sonata in E flat major Op 11 No 1, Ravel's Tzigane, Vitali's Chaconne, Prokofiev's Sonata No 1, Tartini's 'Devil's Trill' Sonata, Szymanowski's Poems-Myths, and Vladigerov's Paraphrase on a theme of the Bulgarian dance 'Horo'. Oistrakh also performed the Tchaikovsky and Beethoven Violin Concertos.

David Oistrakh at the NSW State Conservatorium of Music (now Sydney Conservatorium of Music), 1958.

Thank you to Julie Simonds for allowing me to share this photo.

Oistrakh’s recitals were a great success and were met with ‘unprecedented enthusiasm’, with the Tribune reporting people queuing up from 7am in the hope of getting a returned ticket for one of the last concerts that night. When the Director of the NSW State Conservatorium Bernard Heinze mentioned to David Oistrakh that many students were not able to hear him play, Oistrakh immediately offered to perform a recital for the students. (Although Oistrakh suggested it be free, Heinze insisted a 6 shillings entry fee be paid). The recital was held on 6th July 1958. The Australian violinist Charmian Gadd (then a student) was chosen to make a thank you speech and another student from the Conservatorium High School, called Tanya, translated it.

Recordings of a number of Oistrakh’s Australian concerts were able to reach regional audiences, being broadcast by ABC regional stations. Enthusiasm for Oistrakh’s concerts is also seen in the letter Mona Barry from Canberra had written to the Canberra Times newspaper expressing dissatisfaction to the tour organisers that Canberra had not been included in Oistrakh’s tour.

During his travels through Australia, Oistrakh bought a violin from a ‘Wagga garage proprietor’. The violin was a Stradivarius copy made by the craftsman Arthur Edward Smith in Sydney 20 years earlier.

Oistrakh was welcomed by and became acquainted with many Australian musicians.

David Oistrakh at the NSW State Conservatorium of Music (now Sydney Conservatorium of Music), 1958.

Thank you to Julie Simonds for allowing me to share this photo.

When performing the Tchaikovsky and Beethoven Violin Concertos with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra Oistrakh worked with the conductor Nicolai Malko, with whom he had already collaborated earlier in his career. Charmian Gadd recalls people being moved to tears by Oistrakh playing the slow movement of F. J. Haydn’s Concerto in C major in memory of the French violinist Jacques Thibaud.

David Oistrakh at the NSW State Conservatorium of Music (now Sydney Conservatorium of Music), 1958.

Thank you to Julie Simonds for allowing me to share this photo.

On June 16th at 8pm there was a welcome reception with some 600 guests at the Lower Sydney Town Hall, organised by the Anglo-Soviet Friendship Society. Australian compositions were performed, and the Director of the NSW State Conservatorium of Music Bernard Heinze delivered an address. The Sydney artists taking part in the event included Ian Wilson, Franz Holford, Raymond Hanson, Ian Ritchie and Phyllis McDonald. From his end, Oistrakh responded with a performance of the Prokofiev Sonata for Violin and Piano No 2. After the concert, the composer Alfred Hill presented Oistrakh with the tapes of two of his works and the sheet music of Australian compositions. Earlier on, in Melbourne, there had also been a performance of Australian music organised for Oistrakh to hear, which he was then quoted in the Tribune to have referred to as ‘magnificent Australian music played by first class artists’. And on 6th June, music critics, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, and J. and N. Tait executives, amongst others, welcomed Oistrakh, Yampolskiy and Artemov at the Sydney ABC studio.

It was noted in the press that Oistrakh was looking forward to meeting young Australian musicians particularly Beryl Kimber, whom he had heard at the finals of the Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow earlier that year. Since after the competition there were plans for Kimber to go and study with Oistrakh in Moscow and she did so soon after his Australian tour. Kimber was one of the people meeting Oistrakh and his team and the airport.

David Oistrakh rehearsing with the conductor Nikolai Malko and the Sydney Symphony Orchestra at the ABC studio in Kings Cross, Sydney.

Photograph appears in the book The Rite of Spring: 75 Years of ABC Music-Making by Martin Buzacott, ABC Books, 2007.

Provided here for non-profit research purposes. Please get in touch if there are any issues with it, and the photograph will be removed.

Oistrakh’s connection and influence on the Australian musicians and the Australian music scene did not end there. Alice Waten, currently an Associate Professor in Violin at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, studied with Oistrakh in Moscow. The violinist and composer Wilfred Lehmann performed throughout the USSR on Oistrakh’s invitation. Oistrakh’s visit is also said to have been an inspiration for the composer Larry Sitsky, who later also visited the USSR. While in Australia, on his way to the Kings Cross rehearsal studio for a rehearsal with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra Oistrakh discussed with Charles Buttrose which artists should be invited to Australia, recommending the Soviet violinist Leonid Kogan and the conductor John Hopkins under whose baton he had just played in New Zealand. Kogan did indeed end up giving concerts in Australia in 1962, and Hopkins moved to Australia in 1963, playing a very important role in its musical life. Hopkins also went on to perform in the USSR and in Czechoslovakia on the recommendation of Oistrakh.

One of the photos printed in the brochure for Oistrakh's Australian tour. It depicts David Oistrakh and his wife Tamara Rotareva during a television interview. Thank you to Peter Garrity for sharing the brochure.

Meanwhile on the week of Oistrakh’s departure, after the concert on the night of Monday 7th July, he was presented with an ‘illuminated address bound in green morocco and set amidst the red and gold of waratah and wattle blossom’ contributed to by 200 individuals including those from the music, literary, fine arts, theatre, trade union, and business. It was also signed by members of parliament, heads of banks, a religious leader, and the general secretary of the Communist Party of Australia. Oistrakh responded by saying: “I wish to express my great affection for the audiences of Australia, whose warmth I will always remember with joy”.

Oistrakh’s tour in Australia was by all accounts very successful and left many people with wonderful memories.

Cover of the brochure for Oistrakh's Australian tour. Thank you to Peter Garrity for sharing the brochure.

I would like to thank Charmian Gadd for contributing her reminiscences, Julie Simonds for sharing three of the photos and some of the information presented in this post, and Peter Garrity for sharing the brochure from Oistrakh's tour. To any people who would like to contribute further stories about Oistrakh's time in Australia, I would be more than happy to add them into the post.

Sources:

Australian Music will Sound in Soviet Cities, Tribune, 18 June 1958, 11.

Bright Paper of Australian-Soviet Friendship, Tribune, 30 July 1958, 7.

Buzacott, Martin. The Rite of Spring: 75 Years of ABC Music-Making. ABC Books, 2007.

David Oistrakh, Tribune, 11 June 1958, 6.

David Oistrakh’s Tour, The Canberra Times, 7 June 1958, 2.

Music Lovers will Recall Oistrakh Visit with Joy, Tribune, 9 July 1958, 12.

Oistrakh Buys Australian Violin, The Canberra Times, 8 July 1958, 3.

Oistrakh Here for Concert Tour, The Australian Jewish News, 30 May 1958, 11.

Oistrakh Here on May 27, ABC weekly Vol. 20 No. 21 (21 May 1958), 4.

Oistrakh to Hear Australian Music, Tribune, 4 June 1958, 11.

From the brochure for Oistrakh's Australian tour. Thank you to Peter Garrity for sharing the brochure.

Oistrakh to Tour Here, The Australian Jewish News, 20 December 1957, 12.

Oistrakh’s Violin Made in Moscow, Tribune, 9 July 1958, 7.

Russian Violinist, Victor Harbour Times, 27 June 1958, 6.

Skinner, Graeme. Peter Sculthorpe, The Making of an Australian Composer, UNSW Press, 2015.

Simonds, Julie and Peter McCallum. The Centenary of the Con: A History of the Sydney Conservatorium of Music 1915-2015.

Soviet Violinist in Australia, The Canberra Times, 28 May 1958, 5.

Sitsky, Larry and Ruth Lee Martin. Australian Piano Music of the Twentieth Century (Music Reference Collection), Praeger, 2005, 185.

Stern, Barry. David Oistrakh, The Australian Jewish Times, 11 June 1958, 6.

The Maestro and his Pupil, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 4 June 1958, 4.

“The Pleasure your visit has given us” Australian Thanks to David Oistrakh, Tribune, 9 July 1958, 7.

Tomoff, Kiril. Virtuosi Abroad. Soviet Music and Imperial Competition During the Early Cold War, 1945–1958, Cornell University Press, 2015, 150.

Welcome to Russian Violinist, The Biz, 11 June 1958, 20.

![Vasily Grigoryevich Perov, Receiving the traveller seminarist [Приём странника-семинариста], 1874. https://gallerix.ru/pic/_EX/21028680/700045776.jpeg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54df1055e4b0f4a6ba2c10b5/1599622836511-6F1LBUC5E4Q1QP0IPIX0/image-asset.jpeg)

![Vasily Grigoryevich Perov, Troika [Тройка], 1866, Oil on canvas. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3149337](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54df1055e4b0f4a6ba2c10b5/1599622778733-DTCRVI3X9VS60596NC3U/Troika)